Kettering US airbase's wartime romance secrets revealed by new technology

For two years, Grafton Underwood became home to the United States Air Force (USAF) and at its height nearly 3,000 men and women lived on the site.

During the Second World War romances between local women and US airmen flourished but many of the fathers never got to see the their English children.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThose 'babies' are now in their mid-seventies and have been putting back the missing pieces of their lives.

Thanks to online searches and DNA tests with the children and grandchildren of some of the US airmen have been uncovering the truth about their birth families.

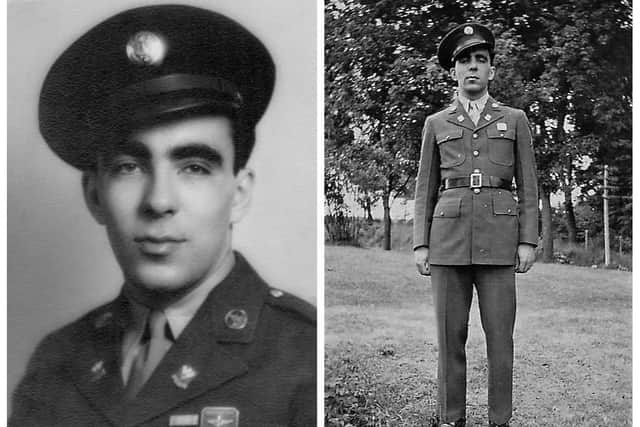

JOSEPH NEAL FUNK

Last year Kettering brothers Haydn and Leigh Kennedy, and their late brother Darren, finally managed to track down their grandfather's family and make contact with their father's blood relatives in the United States.

Their dad Neal Kennedy, born in 1945, had grown up in Kettering knowing that his dad was Joseph Neal Funk, a USAF flight coordinator, who had been based at nearby Grafton Underwood airfield with the 384th Bomb group.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNeal had tried in vain for many years to trace his dad through the Red Cross and even a TV appeal but with no success.

When he was a child he had been taken up to the airbase with his mother Ellen on reunion days in the hope that she would see her beloved 'Joe'.

Neal's sister Melanie Rayner, who was born ten years after Neal, spoke to their mother about her wartime romance.

She said: "She really loved Joe. When our mother met Joe she was in a bad marriage. He paid for her divorce and they actually planned to have my brother and to go back to America to live there.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"But he had to go back to the USA because his mother was in bad health and he told her 'don't write to my mother because she's ill'.

"After a while she moved from Birch Road to Naseby Road in Kettering and then to Northampton. She hadn't heard from him so she thought he'd dropped her."

Although warned not to, new mum Ellen sent letters to his mother with photographs of the young Neal and when she got no reply she tried to contact Joe through the Red Cross.

It took three years for them to get back in contact - the Red Cross told Ellen that Joe had remarried.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMelanie said: "She was really upset. She had sent a letter that he never got and he sent a letter that she never received.

"His wife couldn't have children and Joe offered to raise Neal in America but mum said no."

When Neal was old enough he set to work tracking down his father using the Red Cross, a TV appeal and by using phone books but, as the family found out later, Joe had no permanent phone number listing because he had a job as a travelling salesman.

Haydn said: "Dad kept looking for his father. He tried everything but kept hitting a brick wall. He tried and tried and tried his hardest to find him but couldn't."

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

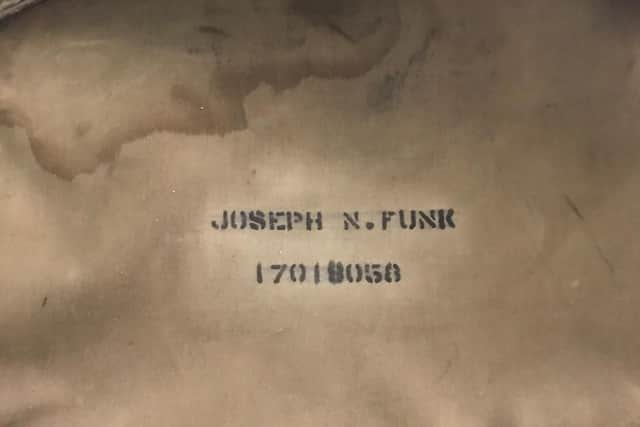

Hide AdNeal died in 1992, without ever meeting his dad. All that he had was his named kit bag that he had left in England, a treasured family heirloom.

Last year Darren had been researching his family tree and found a match for Joe's name and sent a message via Facebook.

The family is now in contact with a cousin in the USA who revealed that Joe had kept photos of Neal, the son he never got to hold, in the family album.

Hayden added: "It just wasn’t possible to find him after an extensive search but the internet has changed all that, and it’s great to now know our family in the States.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor three others their fathers were not lost but a complete surprise. It was through DNA tests that helped three Grafton 'GI babies' trace their biological fathers.

They had no idea that their fathers were in fact American airmen until much later in their lives.

Jerry Phillips, 74, Alan Dickens, 75, and Annie Byles, 76, found out their fathers were US airmen based at Grafton Underwood, through the advances of DNA testing.

Jerry, Annie and Alan had lived all their lives being unaware that Clark Edward Phillips, Eugene Theodore Wilson and William Paige Buckle respectively were their real fathers.

CLARK EDWARD PHILLIPS

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

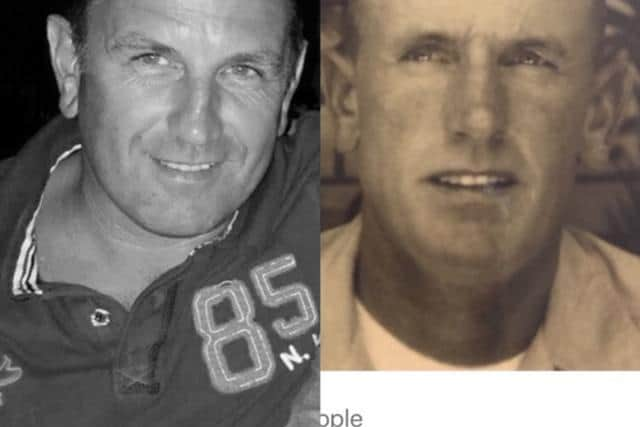

Hide AdGerald 'Jerry' Phillips had grown up being told by his mum that his English father had been killed in the war. Jerry's 18-year-old mum had been living in Thrapston - an easy cycle ride to Grafton Underwood and the airbase - when she fell pregnant. Jerry was born in a home for single mothers in Yorkshire in December 1944 and his mum moved to Peterborough with her new baby.

Michael Phillips (Jerry's son) from Peterborough said: “When my dad was 15, one of my dad's uncles took my dad to one side and said 'never matter what your mum told you, your dad was an American and a tail gunner and he was a really lovely chap'.

“After the war had ended there was quite a bit of shame attached to the girls who had children with the visiting Americans, so in many cases it was hushed up."

It was not until two years ago that Jerry and son Michael decided to take a Y-DNA test to map their paternal ancestry, backed-up by a genealogist.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey discovered a close relative match in America which led them to find the truth that Jerry's dad was Clark Edward Phillips.

He had been stationed at Grafton Underwood for two-and-a-half years, leaving in December 1944.

Michael said: "We had found my dad's brother, uncles and an aunt and his wife - all still alive.

"His wife still had the photo album with loads of photos of Grafton Underwood.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"When asked if Clark had said anything about his time in England he had told them that he 'fell in love with an English girl and he broke her heart'.

"We now know that he was sending food parcels so I think he did know she was pregnant.

"My cousin in America and I have similar temperaments. We share so much. My uncle in America was an only child but now he has a brother."

The family have been reunited by visiting Long Creek in South Carolina where Clark, who died in 1985, is buried in the family plot.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMichael, who owns a building contractor company, has been inspired by his American grandfather to help the Friends of the 384th Bombardment Group uncover and preserve parts of the Grafton Underwood base.

They hope to turn the operations block into a museum as permanent memorial to the US service personnel.

He added: "We're really proud he volunteered. He was the guy that my dad dreamed about. He was a kind, hard-working, generous man. It's almost magical."

EUGENE THEODORE WILSON

Alan Dickens, who grew up in Kettering, discovered that the man he had always assumed was his father was not.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis mum Joan had re-married just after the Second World War but Alan was always curious about his 'real' dad.

He said: "As I approached the age of 74 I decided to try and answer a question that had bothered me since my late teens, was my mother's first husband, my father?

"I only have one memory of meeting my mother's first husband and that was the briefest of encounters in The Market Inn, Kettering, when I was about 15.

"I didn't speak to him and only found out that he was "Mr Dickens" from my stepfather after he had gone.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"When I was getting married we needed to give my father's full name and occupation to the registrar, my mother gave details of her first husband.

"At long last I decided to do something I should have done a long time ago. I applied for a full certificate of my birth registration and my father's name was blank."

Alan recalls that once when he about ten-years-old he was in his grandfather's cafe, which overlooked Kettering market place, when he was sneered at and called a "Yank" by a group of older boys.

After taking a DNA test Alan's results revealed more than 1,000 fourth cousins or closer in the USA.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdUsing the DNA data and associated family trees, Alan's analysis eventually narrowed the search to one of his two sets of great-grandparents hoping to find the others through distant cousins. Then there was a breakthrough.

He came across the entry for a Captain Eugene Theodore Wilson, who went missing in action from the 384th Bomber Group stationed at Grafton Underwood.

Alan said: "In December last year, another second cousin appeared at the top of my DNA match list, a first cousin once removed connected through Eugene's sister.

"This gave me high confidence that Eugene was my father. I initiated an attempt to contact my DNA match hardly daring to hope that she would respond.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"She did and how, far beyond my wildest dreams, commencing with my grandmother, would talk about her youngest brother Eugene all the time. I recall the stories of him and his having gone missing during the war often.

"This first response from my lost cousin turned what had started as an intriguing academic forensic investigation into an emotional thunderstorm of tears and joy far beyond my expectations.

"I've had a fantastic reception from the family. They knew nothing about me but they heard he'd had a girlfriend. He was a navigator on a flying fortress with the 547th Squadronand he had finished his first tour and completed all his missions.

"He volunteered to come back to England for a second tour, possibly to be near to my mother but he was killed on a bombing run to Cologne.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"My wife, Anne, and I have always been puzzled by the long delay between my birth and its registration - two months.

"In the event it was registered six days after he went missing and just one day after the MIA report was dated. I like to believe that they intended to go to the registrar together."

WILLIAM P BUCKLE

Former Wellingborough resident Annie Byles, 76, who now lives in Spain had always known her dad 'Choggy' had been an American pilot and had been told he had been killed in the war.

Her mother Emily, who lived in Scaldwell, worked on the buses in Kettering during the Second World War.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnnie, who was born in 1943 thinks that her parents met at a dance probably at the airbase.

She said: "She told me that he was an American and that she loved him and I think that he loved her."

Two years ago Annie decided to take a DNA test to trace her US family and researched her family tree results revealed she had three siblings - two brothers and a sister.

She said: "My father, William P Buckle, wasn't killed but he was betrothed to someone else. I'm pleased to know that I've got another half. Now I know my father - there's no disputing DNA.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"I think it came as a bit of a surprise for them. My half-brother Tom will be coming over from Texas next year."

She added: “I’m just pleased to now know really who my father was, I don’t feel anything sad at all about the missing years. I just feel proud dad did his duty for our freedom today.”

Neill Howarth is secretary of the 384th Bomb Group UK, a group that helps veterans and their families visit Grafton Underwood.

He said: “The interest in the group is huge and growing all the time due to the internet communication link and these incredible stories of lost family being found.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Boughton Estates have been very helpful in allowing families the access to visit areas that that until recently have been off limits. Everyone is thankful for this.

"It is hoped one day a designated museum and visitor centre could be put at Grafton Underwood. It would be a real asset to the village and the estate."

He added: "Grafton Underwood was where the first and last bombs dropped by the Americans in the Second World War happened so it's a story that needs to be told."

GRAFTON UNDERWOOD DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR

Grafton Underwood's airfield was built in 1941 on a covering around 500 acres of land and was the first airfield in England to receive an Eighth Air Force flying unit, when in May 1942 personnel of the 15th Bomb Squadron took up residence.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe airfield was then home to two squadrons of the 97th Bomb Group and became home to succession of Bomb Groups, including the 305th, 96th, and 384th, all equipped with B-17s of the 97th BG (Heavy).

A total of thirteen separate accommodation and support sites were built including a sick quarters, two sewage plants, a cinema, a large bomb store and two hangers facilities for the more than 3,000 men and women who were based at the site.

On August 9, 1942, Grafton received its first mission orders. On April 25, 1945, the last bombing raids took place over south-east Germany and Czechoslovakia.

In the two years of being at Grafton, the 384th had amassed 9,348 operational sorties, in 314 missions.

They dropped 22,415 tons of explosives and lost 159 aircraft for the shooting down of 165 enemy aircraft.

They received two Distinguished Unit Citations and over 1,000 Distinguished Flying Crosses.